They say it’s the most dangerous country in the world. A territory where poverty, terrorism and nuclear weapons converge. A trip to the most isolated provinces in Pakistan, where the tribe is still the law; to the regions devastated by an earthquake a year ago and the ‘madrasahs’ where the ‘jihadis’ are brought up.

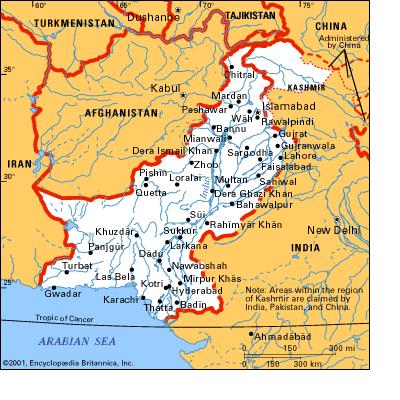

Pakistan

The earthquake lasted 47 seconds. It was like the howl of a dying animal, as a witness who escaped alive remembers. In Jabbar Gali, a remote village four hours away from Islamabad in an all-terrain vehicle, the mosque was one of the first buildings to tumble down. Today, a year after the tragedy, the echo of the call to prayer still thunders in the Siran Valley. The males in the town, dressed the same way they did centuries ago, wear heavy robes of ochre cloth and thick beards died with henna and perform their ritual ablutions in a stream which runs from the peaks. After that they climb the high rocks over the exuberant landscape and they kneel down towards Mecca. The only thing breaking the silence is the roar of the river. It is a deeply spiritual moment. Deserts create prophets and mountains create saints, the anonymous Pakistani teacher accompanying us comments. There isn’t a single woman in sight. They are invisible in this country.

Once prayers are finished, men tell us that the mosque is the first building they want to reconstruct. It is their identity. What gives sense to their lives. We are in the North-West Province. The Pakistani Wild West. A region which spreads between Afghanistan and Kashmir. The two hottest borders on the planet. Poverty, terrorism and nuclear weapons. This isolated and tribal area was devastated by an earthquake on the 8th of October 2005. The final figures were 80,000 dead, 70,000 injured and three million people homeless. When it rains, it pours. In this area, 90% of the population is rural and more than half are illiterate; poverty levels are at almost 60%. In Jabbar Gali 20 out of every 100 women die in childbirth. A higher percentage of girls than boys die before turning five. According to a professional working for Plan, a NGO established in the area back in 1997, who is with us in this trip, states that this is not a biological fact; it’s not that girls are weaker, but rather that they work harder and they are less looked after than boys. Here having a son a blessing from God, but having a daughter is a curse: the dowry has to be paid for her when she marries.

– How does Plan combat such traditions?

– Our goal is to open up women’s eyes: make them be conscious that they have a right to education, health, paid work, justice. A right to live in a healthy environment; to participate in the decision-making. And we are being successful, little by little.

– Is it a religious problem?

– In Pakistan culture and tribalism are added to religion and permeate politics. In Pakistan culture is stronger than religion, because religion is a part of culture.

The work of NGOs is not easy in this country. To start with, they have to overcome the Government’s distrust, not quite inclined to new outside ideas coming in and, once there, it is tricky to manage respecting the complex balance system between tribal, religious and political hierarchies. Tribal law is even above criminal law.

That goes without forgetting that this region is run by the MMA (United Action Front), a coalition of fundamentalist parties which during the 80s took part in the jihad (holy war) against the USSR in Afghanistan; during the 90s they backed terrorism and nowadays, with less noise, they have put their efforts in working for Pakistan to live according to Islamic law. Some experts are already talking about Talibanisation. In certain municipalities, mullahs have forbidden cinema, music, satellite television and foreign press. It is unthinkable for a woman to be out without covering her face. It is impossible to have a drop of alcohol anywhere in the country.

The MMA is not experienced in public management and its electoral program does not devote a single line to unemployment, health, corruption nor the situation of women. Nevertheless, it has successfully yielded profits the deep anti-American feelings generated in Pakistan by the US invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, and its failure in implementing a peace process and reconstructing both countries, in order to erect itself in the country’s third political power and be able to run the two bordering regions with Afghanistan: Balochistān and the North-West Frontier Province. The political weight of the MMA is not determinant in Pakistan yet; on the other hand, it dominates the streets and tele-directs the extensive web of madrasahs (Qur’anic schools) which spreads across the country. These are its big powers.

In such foul environment the earthquake has meant, paradoxically, an opening of the region to the exterior. And a flow of income after ten years of isolation.

When the Taliban reached power in Afghanistan in 1996 the majority of Western abandoned a radicalized Pakistan. The country stopped receiving international cooperation funds. To that loss they would have to add, from 1998 onwards, the international community’s economic sanctions due to the development of the Pakistani nuclear arsenal. The situation became unbearable.

General/President Pervez Musharraf’s (forced) political change of direction towards the United States after the September 11 attacks in 2001 has meant a respite for the country’s precarious economic situation. Bush paid Mush (as the opposition calls Musharraf) for rendered services: around €600 million a year and the renegotiation of part of its external debt. The first NGOs returned to Pakistan in 2002. The earth would still have to shake with the destructive power of a million tons of TNT for large organizations, equipped with 5,000 million euro, to return for the reconstruction. Right now Pakistan’s economy is enjoying one of its best moments in history, with an annual growth rate of 7%. An expansive cycle in which the international community’s support of Musharraf has a lot to do with.

For the inhabitants of the most isolated areas in the region the arrival of tens of international organizations has meant, moreover, their first contact with the feared Westerners; even with women managing teams formed by men. The majority admits that it has been a positive experience. The earthquake has shown them that they can be friends, says a tribal leader. For another local representative, Westerners look like sincere people and, above all, have respected their traditions. They consulted their leaders. And women wore a veil. A third one goes even further and says that they have met Japanese and Germans, who in another time wanted to enslave the world, and instead of coming now to enslave, they have come due to humanitarian reasons.

– Have you met Americans? Are they good people?

– I doubt it. The only country to use the atomic bomb cannot be a good one. Anybody who wants to dominate the world, whatever religion he might belong to, is a terrorist. And we are the last obstacle they have to dominate the world.

Not a single smile. Tanned faces, thick beards, haughty looks. We are in the refugee camp of Daryal, outside Manshera, the district’s capital. Eight local leaders, sitting down in sack-cloth chairs, are answering our questions. They belong to the three clans in the area. They are farmers and small merchants; religious and very conservative people; proud.

Nevertheless, in today’s answers the lukewarm common places abound: calls for fraternity among human beings, the definition of Islam as a peaceful religion. It is difficult to get them out of this calculated ambiguity. They do not involve themselves when alluding to Islamic terrorism: they tell us that the Taliban, Osama and al-Qaeda is politics and tell us to ask the Government.

Communicating with their women is even more difficult. To start with, they do not allow having their picture taken. It is against Islam. The conversation is disappointing. There isn’t a single vindication. Out of the 20 women participating in the meeting, 18 cannot read or write. They are completely covered. They are prematurely aged, burdened with children. They do not look in the eye. Even some of them speak giving us their backs. They are incapable of criticizing men’s dominant role in their society. Only when asked whether it is difficult being a woman in Pakistan the oldest (she could be 50) blurts out: what is very easy is being a man in Pakistan. The last reasoning that one of them gives us is a clone of what a tribal leader has expressed earlier on: they have suffered a catastrophe in our lives; they have been left without a home and their relatives have died. Nevertheless, they keep their values firm.

Faced with this image of submission, it is invigorating to talk to doctor Reda, a 26 year-old female doctor who manages a health centre in the Siran Valley. Reda comes from Peshsawar, the city on the border with Afghanistan where al-Qaeda was born 20 years ago. Where you can still acquire a Kalashnikov for about €20 and where the burqa is law. Doctor Reda represents the other side of the burqa. She wears a thin hijab (veil) and she looks at you in the eye. She presents herself like the new model of Pakistani woman, who owns her own fate: her father trusted her and sent her far away from her house to study. And this is being done by many women in the country.

– It might be the case in large cities, because in Pakistan two thirds of the population still lives in a rural environment…

– Women in rural areas still live secluded in the house; they are second-rate citizens. But people need to be educated. My mission as a doctor also consists in education fathers so that they look after their daughters. And educate women so that they give birth in hospital. I see around 60 patients a day, men and women. I respect them and they respect me.

– What about if a religious man refuses to be seen by a woman?

– I would try to convince a fundamentalist, because I have a very solid foundation.

Doctor Reda is right. It is true, they have advanced a lot. Musharraf has promoted a policy of shares which keeps for women a third of the Administration posts and a 10% of the seats in Parliament. Six months ago a Ministry of the Woman was created. There are women judges and female combat pilots too. Nevertheless, women in Pakistan still face an insurmountable barrier in order to achieve equal rights fully: Hudud, which judges and dictates sentence from a traditional Islamic point of view questions like rape, prostitution, divorce or adultery. And even further, blasphemy or alcoholism.

According to the sinister Hudud, in order to be believed by the authorities a raped woman needs the testimony of four witnesses (men). Otherwise, she can end up in prison for adultery. Theoretically she could even be lapidated. For a man, it is enough to just state three times in his home his wish of getting divorced in order to have it granted. On the contrary, achieving divorce for a woman is a trail of tears which can make her lose custody of her children. Musharraf promised to dismantle Hudud. Another reform of his frozen by the pressure of fundamentalists in the streets.

How is the epicenter of an earthquake like? How does the ground zero of desolation look like? Like a nightmare. It is enough to have a look at Balakot, the picturesque mountain village in which the earthquake started, at 8.50 a.m. on the 5th of October 2005.

The bucolic valley crossed by the Kunhar River is nowadays a ghostly movie set; grey, dirty, sown with ruins and tents through which dark figures wander around. Before the tragedy 70,ooo people lived here; 16,000 died. During that first horrible day the town was cut off from the outside world. Night fell. Torrential rains started pouring down. A neighbour, sitting on an old tire, recounts how the water dragged bodies down the streets. They knew them, they were their friends; pieces of the mountain and trees were falling. They thought that Armageddon had arrived: the end of the world. At the following morning first aid started arriving in military helicopters. Together with them, the bearded ones arrived too: fundamentalists.

It was never a secret in the region. For yeas, this inaccessible part of Pakistan was strewn with Islamist training camps. In the 90s they were talks of up to 60 in the area. They disappeared after S-11. As a university teacher states, Musharraf made them disperse or emigrate to more hidden areas. According to him, there was a time in which, if you were willing to fight, they gave you a weapon and training. Everybody knew about it. He states that there are five secret services operating in the region.

– Which ones?

– The Pakistani ISI, the CIA, el British MI6 and both India’s and China’s secret services. And I don’t rule out the Russians and Israelis.

The police investigation of the Islamic attacks in the London metro in July 2005 showed that at least one of the attackers involved had received military training in that area that same year. Another suspect, arrested by the Americans, confessed to having received training in a camp near Mansehra, which could hold 80 people.

Along the same lines, some survivors confirm that after the earthquake the first ones to arrive to offer aid to the population were Islamic militants. Spending a few hours in the area of Balakot still allows the visitor the transit of old pick-up trucks full of youngsters, some of them wearing camouflage clothing. Nobody knows where they come from or where they are headed to. On the other hand, there is not a single soldier or a policeman to be seen in the area.

In the days following the earthquake, after the initial chaos, the province witnessed a sudden disembarkation of international cooperation organizations. And, without missing a beat, charity organizations united to Pakistani fundamentalist parties followed them: al-Rasheed Trust (accused by the United States of financing terrorist activities), al-Khair Trust and the al-Khidmat Foundation, together with Muslim countries NGOs, like Islamic Relief, alarmed by the perspective of losing their clientele to Western NGOs. These charity organizations have already declared that they are aiming at building 1,500 mosques and 300 ‘madrasahs’ in the area. They are also going to look after the thousands of orphans, another proof of their intentions of talibanising the region.

But this doesn’t mean that all those religious organizations promote terrorism. There is a thin red line dividing Islamic fundamentalism from Islamic terrorism; the groups who fight spiritually, even politically, in order to impose a State governed by the Sharia, from the groups who brandish weapons in order to achieve it.

This division seems to be clear for Pervez Musharraf, who reached power in Pakistan after a military coup in 1999. Musharraf seems to take for granted which fundamentalist groups he can manipulate and, on the other hand, which ones are really dangerous for his permanence in power. He has proven to be a master in the art of double-dealing. He is, on the one hand, a firm ally of the United States in the ‘war on terror’ and, at the same time, supports and uses the religious fundamentalist coalition MMA as an outlet for the population’s dissatisfaction. For an international Pakistani analyst, Musharraf has presented himself to the eyes of the West as indispensable; he has created an image which implies that, should he leave, Pakistan would fall in the hands of terrorists. A diplomat destined in Islamabad picks on this, saying that that would not happen; in reality it is Musharraf himself the one who cannot afford to lose the trust of the international community, which is what keeps him in power. Next elections are due in a year. And we will see then…

Mohamed Yussuf is a step away from crossing that thin red line which separates arguing from shooting. We met him in Balakot’s ruins. He invited us to visit what is left of his house, hanging on the mountain’s slope. There, in what was once his terrace, he ordered his three sons to spread carpets and cushions, to bring cookies and a litre and a half bottle of the local refreshment drink. Muslim’s hospitality in all its expression. Mohamed is a primary school teacher, is 42 and embodies the Taliban stereotype: beard a fist long (as tradition dictates), black clothing and a stern face. He is a compassionate man. His forehead is darkened by big scars, the result of having spent many hours praying, head on the floor. There is no radio in his house, nor television, nor any book other than the Koran. His gestures are slow and self-restrained; his expression is sullen, his discourse has a lilt, all of them looking for the figure of the Prophet Muhammad. He explains that, he, as a Muslim, is not allowed to hate anybody. Peace for him is a duty. We come from far away and he opens his house to us. Islam has never attacked anybody. It has never started any war. But when they are bombarded and their children are killed, they have to answer back. The jihad becomes then an obligation for every good Muslim. And that is not terrorism, it is just defense. Like when they took offense with the cartoons of the Prophet, which made their hearts bleed. Muslims are willing to fight against evil. He finishes repeating that jihad is their obligation.

Jihad, the ambiguous Islamic expression which is immediately related in the Western world with international terrorism, was, nevertheless, a concept practically unknown by Muslims for centuries. Up until the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, that is. Zbigniew Brzezinski, Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor made an unusual war declaration: they were going to mess up the Soviets’ backyard. In a CIA lab somebody resuscitated the concept of jihad as a Muslim community’s holy war against communists. And in that environment were born in history Osama bin Laden and his ‘international brigade’. During the 8os the US press called them ‘Freedom Fighters’. For Fred Halliday, Professor of International Relations in the London School of Economics, the Afghan war was to the 21st century world what the Spanish Civil War was to World War II, the devil’s kitchen in which all the broths which will later poison the world would be prepared.

In the designs of the US’ intelligence services, the Pakistani military dictatorship would be in charge in its own region of brainwashing, training and give logistic support to thousands of jihadists. To that purpose, thousands of madrasahs were opened along the border with Afghanistan: cheap labour for the jihad. And then an accelerated process of Islamisation was carried out in Pakistan, which had been born like a “state of Muslims”, but not like “a Muslim state”. The invention worked. In February 1989 the Soviet army left Afghanistan, and thousands of combat soldiers programmed to kill heathens were left unemployed. In the mean time, the United States washed its hands and left Pakistan to its devices.

Unfortunately, the story of the jihad does not end there. A Pakistani professor explains it to us with the following metaphor: one day the Americans opened the magic bottle, out came the genie and they made a wish, ‘we want to defeat the Soviets!’ The genie granted it. The USSR stumbled and fell. But when he finished its task, the genie didn’t want to go back to the bottle. And he started working for himself. In his words, for the Pakistanis their country was screwed forever.

The mullah Abdul Rashid Ghazi is a symbol of fundamentalism in Pakistan. He boasts that they defeated the Russians in Afghanistan and they are going to defeat the Americans. They are not in a hurry, he says; it took ten years before. Then he asks us whether we know the reason why the United States cannot beat the Muslims, even with all its technology and money. For him, this is because in order to win one has to have courage and principles. The US have 140,000 in Iraq and there isn’t a single one capable of strapping a bomb to his own body and sacrifice himself for his home land. Not even one of them!, he exclaims. On the other hand, Pakistan has thousands of youngsters willing to die, which according to him makes them more powerful. He believes that God is on their side. The mullah crossed the red line decades ago. He runs Islamabad’s Red Mosque and two of the largest madrasahs in the country: Jamia Hafsa and Jamia Faridia, with 10,000 male and female students. His organization, which is thought of being related with al-Qaeda, was an important hook for the jihad during the 80s. He himself fought for three years against the Soviets in Afghanistan. He still carries his Afghan turban with pride. His father, Mohamed Abdullah, was a friend and solid ally of Osama Bin Laden until he was murdered by a rival sect in 1998. In the past two years there have been shootings, assaults and police arrests in this mosque. It has been linked to the President Musharraf’s assassination attempt and the London attacks in 2005. Ghazi has been interrogated several times, but he is still free. And he has his network of 10,000 students between 6 and 20. As he puts it, they do not train students there, they educate them.

So far General Musharraf has failed (once more) in his attempts to bring to light the complex labyrinth of Qur’anic schools abounding in country; the factories of Islamic fundamentalism. His initial intention was to create a government registry, regulate their circle, control their funding and expel foreign students without a visa from Pakistan. Useless. The reform has been postponed indefinitely due to the MMA’s pressing. Nowadays the number of madrasahs in Pakistan is still unknown. The most sensible number could be around 12,000. The number of seminarians is also unknown. Several sources talk about 1.5 million students. With regards to the percentage which predicates violence, the most sensible say around 10% are. Pessimists elevate that number to a third of the total.

As the jihad, madrasahs were initially a reality alien to Pakistanis until the USSR’s invasion of Afghanistan, the moment when the Islamist industry was set up. In 1947, the year of the country’s independence, there were less than 150 schools in the country, while their political influence was zero. In the middle of the campaign against the USSR, during the 80s, they were talking about 2,500. Nowadays some increase the number to 20,000.

The mullah Ghazi refuses to show us his school. He doesn’t want us to disturb the students’ work. As far as the women’s school is concerned, he says not even he enters it: they are given lectures through a microphone, as Islam forbids interaction between men and women. Nature is weak, he says. Nevertheless, he agrees to show us his home. Previously, a seminarian takes out from the room two Kalashnikov rifles, ammunition and guns. He asks us to understand that he has to defend himself from the Government’s terrorist attacks, who seek to please Americans. We are brought cookies and tea. Then he starts his discourse in perfect English. According to him, Islam has spread all over the world very quickly, and the answer from the Western propaganda, which goes against Islam precepts, is to lie, stating that Islam creates intolerance and terrorism. He claims that they respect women, as in they don’t use it as a carnal object. According to the West, Islam ill-treats them, but women have a good life within Islam. He goes on to say that women’s status needs not be changed; it is their culture. They don’t create terrorists either, but in his words, what they do is to educate ulemahs, and they are not taught to attack, but rather defend themselves. Ghazi continues saying that if a Muslim is attacked, his obligation is to extend it across the world. Revenge, to him, is every Muslim’s duty. He says that it is necessary to retaliate with measure: an eye for an eye, nose for nose, ear for ear, tooth for tooth…– Even against civilians, like 9/11?– There is no evidence that it was caused by Afghans, and nevertheless, Bush bombed Afghanistan in retaliation. The US is taking part in this as policeman, judge and executioner. If they have evidence, they need to bring it to the International Criminal Court. But they shouldn’t be invading an innocent country.

– A country which was ruled by people backing up terrorism…

– The Taliban was the ideal government for Afghanistan, but they didn’t have time to implement their program. They weren’t experts in country ruling, they were religious people and the Americans didn’t give them a chance. Islamic law is the ideal f0rm of government. Don’t waste your time going over it, everything is in The Book.

When we finally manage to get into another madrasah, the real picture disappoints us. Muhammadia Ghousia, on the outskirts of Islamabad, is not a sophisticated training camp, but a squalid building in some waste grounds where 300 children and youngsters, many of them orphans and most of them from the most humble backgrounds, between 6 and 18, live in appalling conditions. Here life is very hard. Seminarians get up at dawn. They sleep on mats in the same bare classrooms. While on them, they repeat passages form the Qur’an for hours while they rocks back and forth, pushed but God’s breath, as the rector, Mukhtar Ahmad Zia puts it, whose hand is kissed by the boys passing by. Upon leaving the school they can become religion teachers, go to Islamic University or enter the army. Facing our questions, a 12 year-old seminarian is on the brink of tears. The rector starts to feel uncomfortable with our visit. Wide sweat circles are showing in his tunic. The Qur’an’s lull resonates around the madrasah. Everything looks too poor. But one gets the feeling that this precariousness goes being the mere absence of economic means, but rather that it is part of a complete political indoctrination model.

Pakistan is a powder keg with 160 million inhabitants, half of them under 19. A 97% are Muslims. Half of them are poor. It is ruled by a General who reached power by means of a military coup and who avoids a clean democratic play. The army is a State within the State, secular political parties are discredited by the cases of corruption and fundamentalist parties rule the streets. The country has nuclear weapons. Thousands of Qur’anic schools are unregistered. In the north, the country maintains an almost armed struggle with India (which also owns a nuclear arsenal) for the control of Kashmir. In the west, Pakistan shares a border with Afghanistan which is 1,500 km. long, in many of whose districts there is only a tribal authority. The country is deeply anti-American, is proud of its traditions, admires the Taliban’s practices and thinks that 9/11 was a set-up. But despite all that, the immense McDonald’s between Islamabad and Rawalpindi is jam-packed every night.

And this September Friday, three days before the 5th anniversary of the September 11 attacks in New York, nobody’s bothered by our presence at prayer time in the monumental Shah Faisal Mosque, which can hold up to 1,000,000 people. They ignore us. There are no insults, no threats, we don’t feel uncomfortable nor in danger. When they finish, the worshippers put on their shoes and leave. We see them go in extremely old buses.

Translated from “El polvorín paquistaní”, by Jesús Rodríguez, published in El País Semanal, 5th November 2006 (available inhttp://www.elpais.com/articulo/portada/polvorin/paquistani/elpepusoceps/20061105elpepspor_5/Tes)

[1] Country (long form) Islamic Republic of Pakistan (Islam-i Jamhuriya-e Pakistan)

Capital Islamabad

Total Area 310,402.97 sq mi; 803,940.00 sq km (slightly less than twice the size of California)

Population 144,616,639 (July 2001 est.)

Estimated Population in 2050 267,813,495

Languages Punjabi 48%, Sindhi 12%, Siraiki (a Punjabi variant) 10%, Pashtu 8%, Urdu (official) 8%, Balochi 3%, Hindko 2%, Brahui 1%, English (official and lingua franca of Pakistani elite and most government ministries), Burushaski, and other 8%

Literacy 42.7% total, 55.3% male, 29% female (1998)

Religions Muslim 97% (Sunni 77%, Shi’a 20%), Christian, Hindu, and other 3%

Life Expectancy 60.61 male, 62.32 female (2001 est.)

Government Type federal republic

Currency 1 Pakistani rupee (PRe) = 100 paisa

GDP (per capita) $2,000 (2000 est.)

Industry textiles, food processing, beverages, construction materials, clothing, paper products, shrimp

Agriculture cotton, wheat, rice, sugarcane, fruits, vegetables; milk, beef, mutton, eggs

Arable Land 27%

Natural Resources land, extensive natural gas reserves, limited petroleum, poor quality coal, iron ore, copper, salt, limestone

[Source: http://go.hrw.com/atlas/norm_htm/pakistan.htm. (Translator’s note.)]